Mount St. Helens. Say her name and it instantly draws to mind images of the cataclysmic eruption of 1980. We all remember the news footage and heart-stopping images of the fiery blast. Americans as far away as Florida had at least a dusting of ash on their cars. Fifty-seven people lost their lives, and the infamous eruption’s impact has lasted to this day. Mount St. Helens has erupted before and since 1980, and has quite the track record to explore. So before we head out on our adventures with the volcano, let’s go on a whirlwind trip through time to get a better understanding of Mount St. Helens.

Mount St. Helens is a composite volcano in the Cascade Arc and is by far the most active of the group. Located in Washington State, the volcano is about 50 miles northeast of Portland, Oregon and 30 miles west of Mount Adams.

Volcanologists believe that Mount St. Helens started its volcanic shenanigans around 40,000 years ago, which is relatively young compared to the other composite volcanoes in the area. But the real action started around 2,500 – 3,000 years ago. Thanks to the Juan de Fuca plate subducting under the North American plate, Mount St. Helens is continually fueled by the melting materials in the crust. This gives the volcano plenty of mojo for its eruptions!

Composite volcanoes are known for their explosive tendencies, and Mount St. Helens is certainly no different. The volcano’s lava tends to be a mix of dacite, rhyolite, and andesite. All three of these lavas are very sticky and explosive. There have been at least two basalt lava flows on Mount St. Helens, one of which left behind the third largest lava tube in North America.

Eruptive Periods

Mount St. Helens has had four distinct eruptive periods. Each period is separated by stretches of time where the volcano was completely quiet. Much of the material from older eruptive periods has been destroyed or buried by more recent eruptions, making it difficult to fully understand those periods.

Ape Canyon Stage (275 – 35 thousand years ago)

A series of lava domes erupted during this time. Ash from these eruptions has been found in central Washington, which suggests that the eruptions were explosive.

Cougar Stage (28 – 18 ka)

Volcanologists believe that this was the second most active stage in Mount St. Helens’ history. Evidence remains of tremendous lahars, pyroclastic flows, ash clouds, lava flows, and a debris avalanche. The debris avalanche from this stage is believed to be even larger than the landslide that started Mount St. Helens’ 1980 eruption. And like the 1980 eruption, the debris avalanche in the Cougar Stage initiated an explosive eruption that ejected pyroclastic flows and ash that buried the landslide in 300 feet of pumice.

Near the end of the stage, Mount St. Helens produced the largest lava flow in the mountain’s history. Known as the Swift Creek Flow, this andesitic lava flow was 650 feet (200 m) thick and flowed 3.7 miles (6 km) down Swift Creek, damming river channels and causing flooding.

Swift Creek Stage (16 – 12.8 ka)

This stage was characterized by the creation of a number of lava domes on and around the volcano. Some of the domes were created explosively, as shown by a number of pyroclastic deposits that fan away from the volcano.

Spirit Lake Stage (3,900 – present)

Most of Mount St. Helens’ cone – as we knew it before 1980, anyway – was created during this stage. Repeated dacite, rhyolite, and andesite eruptions built the cone into its stunning shape. In this current stage, there are seven distinct eruptive periods: Smith Creek, Pine Creek, Castle Creek, Sugar Bowl, Kalama, Goat Rocks, and the Modern Eruptive Period.

Want the nitty gritty details on each of these eruptive periods? This USGS page is a great spot to nerd out!

https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/volcanoes/st_helens/st_helens_geo_hist_108.html

In the meantime, let’s focus in on the Modern Eruptive Period. (Because I know you want to know more about the volcano blowing her top!)

The Modern Eruptive Era – May 18, 1980

Mount St. Helens is as spunky as they come. The most active volcano in the Cascades, locals to the region are no stranger to her shenanigans. First Peoples tell legends of the mountain that housed a sacred fire. After Captain Vancouver and Lewis and Clark explored the area and saw the steaming aftermath of eruptions. Settlers to the area learned to live with the volcano’s frequent quakes and emissions. The last eruption before 1980 was in 1857, and that gave everyone plenty of time to forget what the volcano could really do.

Over the century that the volcano remained quiet, snow and glaciers blanketed the volcano’s steep cone. Homes and towns built up around the base of the peak, and camps and recreational areas became popular. People flocked to the area each year to camp, hike, and enjoy the outdoors.

In March of 1980, the University of Washington began tracking earthquakes beneath Mount St. Helens. One or two earthquakes might not have been a concern, but as each day passed, the number of quakes shot up until there were hundreds each day. Magma had begun to accumulate in the volcano, but it didn’t do so in the way the volcanologists expected.

On March 27, Mount St. Helens had its first eruption in over a century. Ash and steam burst from the summit. A crater widened to 1,300 feet and cracks ran up and down the summit area. The eruption stopped on April 22 and paused until May 7. A series of tiny eruptions continued to spout from the summit but, in the meantime, an enormous bulge was growing on the north slope of the volcano and becoming increasingly unstable.

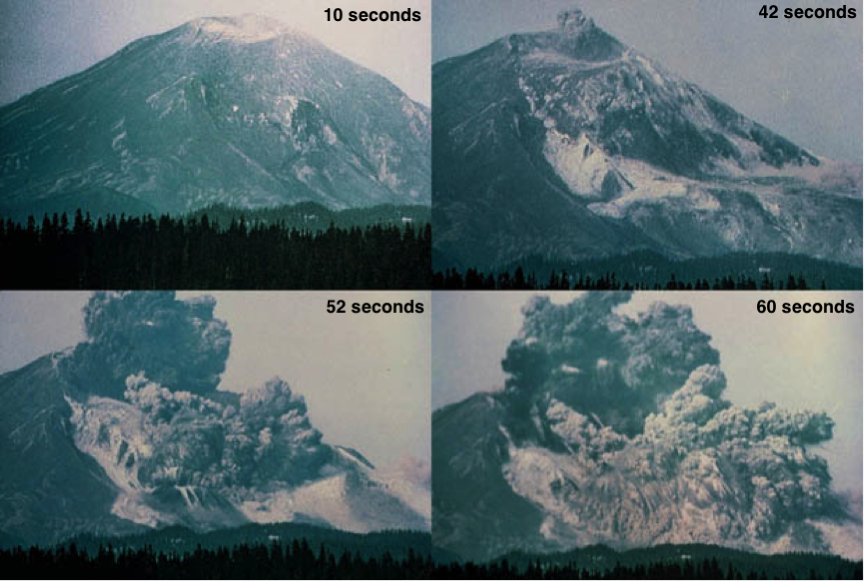

At 8:32 am on Sunday, May 18, a 5.1 earthquake shook the volcano. The earthquake triggered an enormous debris avalanche on the north flank of the volcano. The landslide released the pressure inside Mount St. Helens like a shaken up soda bottle. The volcano erupted in a lateral blast, shooting pyroclastic materials to the north instead of directly up into the atmosphere. Forests were completely leveled; trees were ripped from their roots. The landscape and everything in it was scorched. Hikers on Mt. Rainier and Mt. Adams felt the temperature shoot up 50 degrees. Snow melted beneath their boots.

Pyroclastic flows swept down the north side of the volcano. Ash rose 80,000’ feet into the air. Spokane, WA saw complete darkness in the middle of the day. Ash visibly fell through the midwest and the cloud circled the globe in just 2 weeks.

As the snow and glaciers on the volcano melted, they created a concrete-like mudflow called a lahar. The lahars swept through the river valleys, taking everything in their path along with them: cars, trees, bridges, houses. The mudflows and volcanic debris eventually even reached the massive Columbia River, filling it with so much debris and sediment they had to dredge the river.

But Mount St. Helens wasn’t done there. The volcano had further eruptions and pyroclastic flows in June, July, August and October of 1980. It continued to erupt until 1986. Then the mountain took a breather. Between 1989 and 2001, hydrothermal explosions occurred on the volcano, but they weren’t a result of rising magma. Instead, they were caused by superheated groundwater breaking through the rock. Then the volcano got quiet.

In 2004, Mount St. Helens burst back onto the stage for her encore. The volcano began to erupt again after three years of practically no seismicity. During this 4 year eruption, only 2 notable explosive events occurred. Overall, the eruption was characterized by the growth of the lava dome in the center of the crater.

Today, Mount St. Helens is not currently erupting, but the volcano is still active. Small earthquakes happen all the time, and occasional earthquake swarms suggest magma movement and the magma chamber refilling under the mountain.

Mount St. Helens is constantly changing and moving, and will most certainly erupt again. With this understanding of the volcano’s history under our belts, we are ready to go and share an adventure with her, and finally meet the mountain face to face.

Next up: Mount St. Helens: Spirit Lake Memorial Highway to Johnston Ridge Observatory (Part 1)

Copyright © 2019 Volcano Hopper. All rights reserved.

Loved this post? Share it!