After discovering that the La Garita eruption – the largest explosive eruption in the history of the Earth – was essentially in my own backyard, I had to explore it. The caldera itself is massive, well over a thousand square miles. It would take me years to explore it all on foot. For now, I decided to focus in on one of the most obvious traces of the ancient eruption: Wheeler Geologic Area.

Wheeler Geologic Area is tucked away deep in the La Garita Wilderness in southwestern Colorado. When La Garita erupted, huge amounts of ash and pyroclasts fell out here. The heavy ash compressed together and became volcanic tuff. Now named the Fish Canyon Tuff, Wheeler has been well protected over the millennia by the deep valley where it fell. Erosion has carved away at the tuff deposit over the years, leaving spectacular formations of gray and white behind.

We had tried to plan our adventure to Wheeler Geologic Area for several years after I discovered the existence of La Garita. Monsoon rains and raging wildfires kept us from making the trek until, in 2017, we got our chance. The hike to and from Wheeler Geologic area is a long 8 miles; 16 round trip. But the views and volcanic formations that we saw along the way were absolutely worth it, even if it was one “tuff” hike.

All My Bags are Packed

Since the hike to Wheeler Geologic Area is a long, full day trek, we needed to be sure that we were well prepared. Here are some essentials that we took on our trip:

Plenty of Food and Water:

We made sure we had enough food for the whole day, plus an extra meal in case something unexpected happened and we were stuck outside overnight. Everyone packed high protein snacks, some carbs, and even some sport jelly beans for those moments we needed a little boost. Each person carried 4 liters of water; by the time we returned to trailhead, our water was nearly empty.

Sun Protection:

The sun is very intense at high altitudes. While it may feel cool outside, the sun can burn you much more quickly than at sea level. We made sure to apply sunscreen routinely throughout the day, and wore long sleeves and a hat to provide extra protection. Packing some bug spray is also handy for traversing the forests.

Toilet Paper:

The only toilet to be found in this area is at the Hanson’s Mill trailhead. Make sure to take some toilet paper and a shovel so that you can bury your business in the woods.

Good Gear:

Make sure that you have really good hiking shoes and clothing. Be sure to break it in before your hike. New gear can cause blisters in places you didn’t know you had. Hiking poles are not a necessity for this hike, but can certainly come in handy for the steep sections. Bring a poncho and/or extra layers. Think about bringing along a tarp or small tent that you can set up for a quick shelter if the weather looks questionable. The weather can change and the temperature can swing quickly. A compass is always helpful to have on hand.

Light:

Regardless of whether you are camping or not, bring a headlamp or some flashlights and extra batteries. This hike is long and you could find yourself outside after dark if your return is delayed. On our trip, we came skidding in to Hanson’s Mill right at dusk.

Camping Gear:

If you don’t want to make the trip all in one day (which is what I plan to do next time we go explore Wheeler), you can camp right outside of Wheeler Geologic Area. Make sure you bring along good camping gear and warm layers for night. Be a good steward of the land and mind your campfire and pack out your trash.

Camera:

The views on this hike are stunning. Be sure to chronicle your trip and bring along a camera or two.

Hanson’s Mill

The trailhead to Wheeler Geologic Area is deep in the heart of Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. About 10 miles southeast of silver mining town, Creede, is a turn off for Pool Table Road. This gravel road winds ten miles, climbing to an elevation of 10,840 above sea level. The views are fantastic and, if you keep your eyes peeled, you might see some mountain goats or big horn sheep grazing in the valleys below. We took the drive shortly after sunrise, our car kicking up plenty of dust behind us as we wound through the mountains and enjoyed the views.

Pool Table Road ends and the trails start at an area called Hanson’s Mill. This place is all that remains of an old sawmill that used to be in the area. Now, all that is here is a parking lot, an old pile of sawdust, some space for some camping, and a pit toilet.

From Hanson’s Mill, there are two ways to get to Wheeler:

4-Wheel Drive

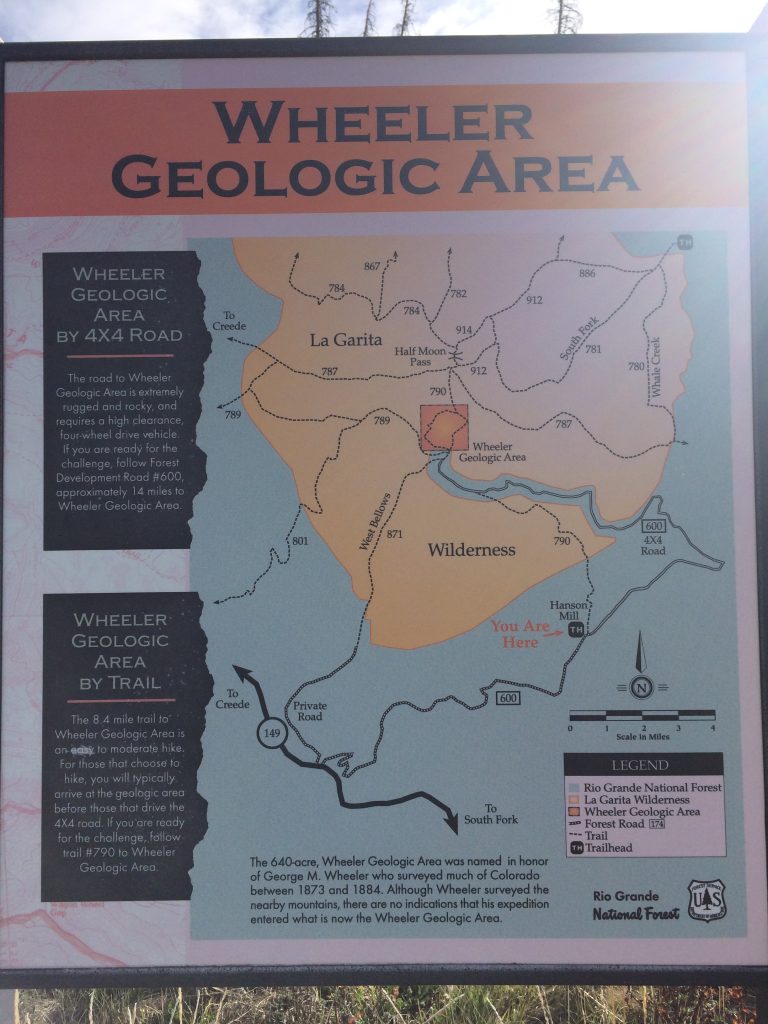

First, you can take a 4-wheel drive vehicle 14 miles down the narrow and winding Forest Service Road 600. This road is heavily eroded with gullies and potholes everywhere. When it rains, it can become very slick and sometimes impassible.

Note: Do NOT try to drive your car down this road – you will get stuck and destroy your car. Even with a Jeep, this is a tricky drive. All of the people we met used dirt bikes or ATVs. You don’t want to get stuck out here. It’s a long hike back to town. Did I mention that there is zero cell phone reception?

Hiking

The other way to get to Wheeler Geologic Area is by hiking the 16-mile round trip trail.

The five of us chose to take a hike. Paul and Alex (remember them from our Mount St. Helens adventures?) were excited to join Jason and I on another volcanic hike. I think we’re starting to make this a tradition! Adding to our hiking group was Kim – a guy who loves being in the mountains more than any other person I know. We share a love of geology and so we were glad to have him join us on our adventure.

All five of us were all in excellent shape, had hiked at altitude before, and were excited to get off the beaten path.

Through the Woods

Finding the trail just to the left of the forest service road, we headed through the thick layer of pine needles to start our adventure! The trail gently meandered through a thick forest of evergreen trees and scrub oak. In the summer, as we discovered, bright flowers of all shapes and colors blossom in the underbrush. Purple columbines popped up here and there. Animals rustled behind trees and birds hopped from branch to branch. There wasn’t a soul in sight.

After a mile or so, the trail begins to work its way downhill. Suddenly, the forest opened up in front of us to reveal a massive ravine. An enormous basalt lava flow had once burst from a fissure uphill and had gushed down this ravine. Eventually, it had solidified where it ran. Now, huge chunks of black basalt and spatters of cinder fill the area. I can only imagine watching this red hot flow racing down the ravine, spattering with energy as it burst from the fissure. It must have been a sight.

Since the flow was relatively untouched and unburied, it suggested to us that this basalt flow had been created after the enormous La Garita eruption. We crossed through the heart of it on the trail and investigated the lava.

As the trail continued, it came across several other similar basalt lava flows. The forest and undergrowth hid some of the flows, but others were clearly visible against the alpine landscape.

The trail became steeper and we approached a section of switchbacks leading down to the valley below. At the bottom of the hill, the valley stretched wide in front of us and offered us some spectacular views.

Over the River

A river gently winds through the flat valley at the bottom of the switchbacks. An old wood sign reads, “La Garita Wilderness.” Out here, it really does feel like wilderness. There is no cell phone reception and no other trace that humankind has ever set foot here. Cattails and flower spring up everywhere. Water gurgles in the river as it runs over old lava. Mountain peaks are visible in the distance. It was a beautiful place to rest for a few minutes and enjoy the scenery. But we had a long way to go.

Our next challenge was crossing the river. There is no bridge or path that leads over the water. We scouted the area for a few minutes and picked the path of least resistance. A narrow log stretched between the two shores. Using a long, thick branch for added balance, each of us tightrope walked our way across the log to the other side. We jokingly took bets about who would be the first to take a swim; no one got to cash in.

A “Tuff” Climb

From the valley, the trail takes a sharp turn up. The hike was very steep as we continued to gain elevation. The forest vanished, allowing us to clearly see the landscape around us. Cinder cones and old lava domes had pushed their way up through the ground. Old lava flows ran this way and that along the steep hillside. Many had oxidized, turning the ground the color of rust. And the trail continued climbing.

Alpine

Reaching the top of the incline, the trail flattened out. What a relief! Our quads were definitely burning after climbing at least 1,000 feet. It was almost as steep as Monitor Ridge on Mount St. Helens for parts of the climb.

Now, we had come out on a flat plateau. Summer flowers dotted the grassy alpine landscape. Views of other mountains – still with snow on their peaks – filled the horizon. Many of the mountains in the San Juans have volcanic pasts. For example, Snowshoe Mountain near Creede is a resurgent lava dome.

Being in the heart of La Garita, I knew that many of the hills and valleys we saw were created by the series of enormous eruptions that the volcano once produced. It was mind-blowing to know that this whole area had once exploded with a force never before seen by mankind. This whole wilderness – with all its trees and wildlife – masks an enormously powerful volcano. Though La Garita is considered extinct today, the ripples of what happened here can still be felt if you’re paying attention.

Reaching the opposite side of the plateau, the trail we had been hiking joined with the forest service road. It began to steeply decline in elevation as we continued into a deep valley.

Down in the Valley

We were surprised how gnarly the 4WD road really was. Huge potholes were gouged out of the dark mud and whole sections had completely fallen away into the nearby ravine. As we entered the forest again, the mud gave way to sand that mixed with gray ash. Our boots slipped in the loose material as we continued hiking.

The forest breaks as the trail levels out at the bottom of the valley. Glimpses of Wheeler’s cream-colored formations peeked out from behind a cluster of trees. The trail looped around like a giant horseshoe then, before we knew it, we have arrived!

Fences separated a small campground from Wheeler Geologic Area. The five of us found some felled logs where we sat down and ravenously dug into a picnic lunch. Our feet were already a little sore from the intense hike. We had come approximately 8 miles and it was just after noon. We would have only a couple of hours to explore the Fish Canyon Tuff before we needed to hustle back.

Looking up at the white spires peeking over the trees, we were more than ready to go explore the immense tuff deposit. I couldn’t believe we were standing beneath the one of the most visible remnants of the most explosive eruption in Earth’s history.

Up Next: Wheeler Geologic Area

Copyright © 2020 Volcano Hopper. All rights reserved.

Loved this post? Share it!