Mount St. Helens is one of the most fiesty volcanoes on the planet. It is certainly one of the most active volcanoes in the United States. Situated in Washington’s Cascade Range, this stratovolcano is known for its explosive and frequent eruptions. Mount St. Helens has produced lava flows, towering lava domes, and erupted roiling ash clouds and pyroclastic density currents. Out of all of Mount St. Helens’ eruptions, one event in particular has branded itself into our memories: the eruption on May 18, 1980.

May 18, 1980

It was a quiet and sunny Sunday morning in Washington. Birds were singing in the thick forest and trout were splashing in the Toutle River. Elk roamed through the underbrush. And Mount St. Helens conical peak dominated the landscape.

Since March 1980, frequent earthquakes had rattled the volcano and surrounding landscape. Several small eruptions of gas and ash had occurred at the summit in recent weeks. More startling was the way Mount St. Helens had begun to deform. A tremendous bulge had formed under the north slope of the mountain in a matter of weeks.

Scientists and local government officials had never seen anything quiet like it. They understood that Mount St. Helens was active, but the last eruption had been in 1857. No one alive had witnessed the potential power behind the volcano. They frantically studied the mountain and try to predict what type of eruption the volcano would produce – and when.

The area surrounding Mount St. Helens was home to a YMCA camp, several lodges, and many residences. It was a popular spot for outdoor activities and for people wanting to vacation. The surrounding forest was also a prime location for foresting.

In previous weeks, people had been evacuated from the area surrounding the volcano. They were eager to return to their homes and jobs. Despite the warning signs that Mount St. Helens was waking, many people had chosen to camp near the mountain that weekend. Loggers were working extra hours to make up for lost time. Photographers camped out to capture the volcano during the early hours. Scientists manned their observation posts. Most of these people were over 5 miles away from the volcano, maintaining a distance they thought would be safe.

8:32 A.M.

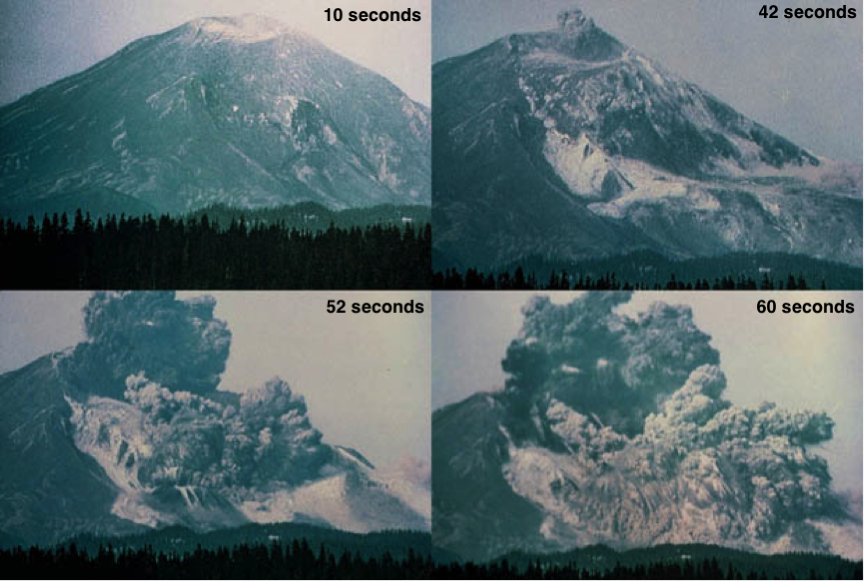

At 8:32 A.M., a magnitude 5.1 earthquake rattled the landscape. The quake shook the unstable bulge on the mountain’s north face and a massive landslide ensued. The sudden absence of rock released the pressure that had been building inside Mount St. Helens. Pyroclastic density currents, lava and ash exploded outward like a shaken soda bottle. What had once been thick forest was flattened and covered in volcanic material. The tremendous heat of the eruption could be felt up to 80 miles away by hikers on Mt. Rainier. Volcanic mudflows called lahars swept away homes and bridges, burying everything they came in contact with. Rivers as far away as the Columbia River in Portland clogged with silt and breached their banks.

The blast from Mount St Helens devastated an area nearly 20 miles north of the volcano. Several survivors escaped from the eruption. Their stories are heart-wrenching and hair-raising. Fifty-seven people, however, perished in the eruption. Among them were campers, loggers, photographers, residents, and a volcanologist. The eruption on May 18 was the deadliest volcanic eruption in United States history.

Mount St. Helens Today

Mount St. Helens continued to erupt after the initial blast on May 18, 1980, sending multiple pyroclastic flows and ash clouds into the air. Five more explosive events occurred in the summer and fall of 1980, sending further pyroclastic flows racing into an area north of the volcano called the Pumice Plain. Between late 1980 and 1986, hundreds of explosive events created a new lava dome in the heart of the volcano. While showing signs of activity, Mount St. Helens didn’t erupt again until 2004. The latest eruption phase lasted until 2008.

Today, Mount St. Helens sits quietly – more or less. Seismic events are common beneath the volcano and scientists are constantly monitoring the volcano’s inflation, deformation, and gas emissions. Mount St. Helens will certainly erupt again, but at this point, no one knows how intensely the eruption will be or when it will happen.

Exploring Mount St. Helens

I’ve longed to explore Mount St. Helens since I was a kid. Just a few months shy of the 40th Anniversary of the eruption, we were fortunate to visit and explore the volcano.

The scars from the May 18theruption are still tangible. The forest has been knocked flat. Trees lay like matchsticks across the landscape and enormous boulders jut up from the grasses. Small trees are beginning to take hold of the landscape and grow, but the blast zone looks more like an alpine area than a forest. Colorful wildflowers cover the landscape in the late summer and grasses wave in the wind. Closer to the foot of the volcano, hummocks (chunks of the mountain) and thick pyroclastic deposits cover the earth.

The volcano’s north face sits open; a window into the crater. The lava dome at its heart has been steadily growing and is steaming happily away. Mount St. Helens is beautiful – and deadly.

If you want to learn more about Mount St. Helens and the treasures we discovered on our adventures, check out these articles:

- A Trip Through Time

- Spirit Lake Memorial Highway

- Johnston Ridge

- The Boundary Trail

- Monitor Ridge to the Summit

- The Summit

A Standout Eruption

Of all the eruptions that Mount St. Helens has had – and will have in the future – why does the May 18, 1980 eruption stand out? How has it branded itself on our memory and cultural consciousness? Here are a few reasons why that eruption was so important.

Visibility

Mount St. Helens’ eruption was very visible. Unlike eruptions in remote landscapes, such as Alaska, this volcano is easily accessible and can be seen from miles away. Thousands of witnesses to the eruption have not only shared their stories, but have shared photographs and videos of the event. We have the advantage, even 40 years later, of seeing the eruption unfold with our own eyes. With our ability to communicate this story – through televised news, radio, and printed collateral – news of the eruption quickly spread around the world. It is one of the best documented volcanic eruptions in the United States, maybe even the world.

The Most Economically Destructive

Mount St. Helens was the most economically devastating eruption in the United States. Homes and businesses near the volcano were wiped off of the map. Ashfall caused significant health and breathing issues for people miles away and caused damage to buildings, machinery, and vehicles. Rivers as far away as the Columbia River were flooded with silt and debris and needed to be dredged. Bridges and roads were in need of rebuilding. Flights were cancelled or diverted. States across the country reported ashfall. Billions of dollars were spent to clean up and repair the damage caused by Mount St. Helens’ eruption.

The Deadliest Eruption

Worse than the economic destruction was the loss of life from the May 18 eruption. Fifty-seven people were killed when the volcano erupted. Some of them were never found. Many others suffered critical injuries from the eruption and faced months, even years, of recovery.

Disaster Planning and Recovery

Everyone knew that Mount St. Helens was an active volcano. Scientists had researched the volcano for years and had warned in 1978 that it would erupt before the end of the century. Plans in preparation for such an event had been drafted but, when push came to shove, were they actually followed?

Government officials were put in a difficult position when Mount St. Helens began to show activity in March. There were so many unknowns. Even though the volcano was becoming restless, would it actually erupt? Some people believed there was no danger. Others advised otherwise. No one knew the scale of the eruption that was coming. After weeks of evacuation orders and restrictions, residents and business owners were growing restless and wanted to return to their properties. Relaxing restrictions could mean greater casualties. It was a no-win scenario.

Looking back at the months surrounding the eruption can be a learning opportunity for how residents and local governments might handle an impending volcanic eruption. Many active volcanoes have large populations surrounding them. It’s almost a guarantee that circumstances like this will arise again.

A New Understanding of Volcanology

Our understanding of volcanoes is ever-changing. Scientists are constantly learning new things about how different volcanoes behave and which mechanisms might cause eruptions. There is still so much to learn, but Mount St. Helens gave us so much information about stratovolcanoes and what makes them tick.

Volcano monitoring and understanding has changed and improved significantly in the last 40 years thanks to the things we have learned at Mount St. Helens. Before 1980, the only volcano observatory in the United States was in Hawaii. Now, there are five – including the Cascades Volcano Observatory that monitors Mount St. Helens and its neighboring volcanoes.

Studies of Mount St. Helens’ have provided scientists with a better understanding of how volcanoes work. There have been great advances in gas and seismic studies, how magma moves through a volcano’s vents, and the behavior of pyroclastic density currents, just to name a few.

Final Thoughts

The eruption of Mount St. Helens on May 18, 1980 is an event that will live in our memories for a long time. It is a breathtaking example of just how powerful a volcano can be. 40 years later, we remember those who were lost in the eruption, and those who survived. And we study the past so that we can prepare better for future eruptions at Mount St. Helens and other volcanoes.

In Memory

In memory of those who lost their lives in the May 18, 1980 eruption:

Reid Blackburn. Wallace Bowers. Terry Crall. Joel Colten. Ronald Conner. Clyde Croft. Jose Dias. Ellen Dill. Arlene Edwards. Jolene Edwards. Bruce Faddis. James Fitzgerald. Thomas Gadwa. Allen Handy. Paul Hiatt. David Johnston. Andrew Karr. Bradley Karr. Michael Karr. Robert Kasewater. ChristyKillian. John Killian. Harold (Butch) Kirkpatrick. Joyce Kirkpatrick. Robert Landsburg. Robert Lynds. Gerald Martin. Gerald Moore. Keith Moore. Shirley Moore. Kevin Morris. Michele Morris. Edward Murphy. Eleanor Murphy. Donald Parker. Jean Parker. Natalie Parker. Richard Parker. William Parker. Merlin Pluard. Ruth Pluard. Fred Rollins. Margery Rollins. Paul Schmidt. Barbara Seibold. Ronald Siebold. Donald Selby. Evlanty Sharipoff. Leonty Skorohodoff. Dale Thayer. Harry Truman. James Tute. Velvetia Tute. Karen Varner. Beverly Wetherald. Klaus Zimmerman.

Copyright © 2020 Volcano Hopper. All rights reserved.